When undertaking research for my book, ‘Murder at the Regatta,’ my characters visited St Mary’s Church in Henley. It was while researching the church online that I discovered a real-life Henley murderer was buried in the grounds of the church. I didn’t have space in the book, neither would it have fitted with the story, to include Mary Blandy’s tale. It does, however, make for an interesting blog post. So here it is. For those amateur detectives among you, the question is: guilty or not guilty?

The Poisoner of Henley: A Tale of Love, Deception, and Disputed Innocence

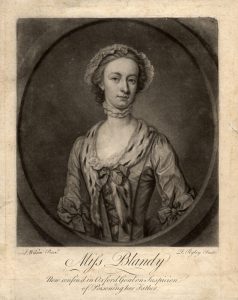

On the morning of April 6th, 1752, at the age of 32, a young gentlewoman named Mary Blandy ascended the steps of Oxford Castle’s gallows, her face pale but composed. As the crowd gathered to witness her execution, she made one final declaration: “For the sake of my father’s memory and my mother’s name, I declare that I am innocent!”

This was not the first time Mary Blandy had proclaimed her innocence, nor would it be the last – her ghost, some say, still haunts parts of Henley, endlessly protesting her guiltlessness in one of the most notorious poisoning cases of the 18th century.

The Beginning: A Father’s Pride

Mary was the only surviving child of Francis Blandy, a respected attorney and town clerk of Henley-on-Thames. Educated, witty, and accomplished, she was her father’s pride and joy. Francis Blandy frequently boasted that his daughter would come with a dowry of £10,000 – a fortune that attracted many suitors to their handsome Georgian home on Hart Street.

Enter the Captain

In 1746, Captain William Henry Cranstoun, a charismatic Scottish noble’s son, swept into Mary’s life. Despite his aristocratic connections, Cranstoun hid dark secrets: he was already married to a Scottish woman, though he claimed the marriage was invalid. Francis Blandy, initially impressed by Cranstoun’s titled background, grew increasingly suspicious of the captain’s intentions and refused to sanction the marriage.

The Potion Plot

What happened next became the subject of endless speculation and debate. Cranstoun sent Mary mysterious packages from Scotland containing what he called “love powders” – supposedly to soften her father’s opposition to their marriage. Mary began adding these powders to her father’s tea and food.

The powder was, in fact, arsenic.

Her Father’s Slow Death

Francis Blandy began experiencing symptoms in summer 1751: burning throat, nausea, and excruciating stomach pains. As his condition worsened, their maid, Susan Gunnel, grew suspicious of the white powder she had seen Mary stirring into her father’s gruel.

On August 14, 1751, Francis Blandy died.

Protest of Innocence

Arrested and tried at Oxford Assizes, Mary maintained that she had no knowledge the powders were poisonous. She insisted Cranstoun had told her they were a type of love philter meant to make her father more amenable to their marriage. Her defense was passionate and articulate, but the evidence was damning.

Even in prison, she wrote a detailed account of her case titled “Miss Mary Blandy’s Own Account of the Affair between Her and Mr. Cranstoun.” In it, she painted herself as a victim of Cranstoun’s manipulation, suggesting he had used her affection to orchestrate her father’s murder.

The Final Scene

On that April morning in 1752, Mary Blandy met her fate with remarkable composure. Dressed in black, she reportedly fretted about whether the wind would disarrange her dress on the scaffold – a detail that speaks to either remarkable sangfroid or complete denial.

Her last words on the scaffold were precise and deliberate: “I am innocent of any intention to kill my father.”

The Aftermath

Captain Cranstoun, the man who had sent the fatal powders, fled to France and died in obscurity months later. Mary Blandy’s case became a sensation, spawning numerous pamphlets, ballads, and debates about her guilt or innocence.

To this day, historians and true crime enthusiasts debate: Was Mary Blandy a cold-blooded murderer who killed for love and money? Or was she, as she claimed until her last breath, an innocent dupe manipulated by a cunning scoundrel?

The truth lies somewhere in the murky waters of the Thames that flows past Henley, where Mary once walked as a respected gentlewoman, before arsenic and ambition – or love and naiveté – sealed her fate.

—

While this account maintains historical accuracy regarding the key events, some dialogue and atmospheric details have been sensitively elaborated to enhance the flow. The core facts – Mary’s relationship with Cranstoun, her father’s poisoning, her consistent claims of innocence, and her execution – are all documented historical events. Over to you: guilty or not guilty?